##Update##

The fundraiser has passed $1Million. Wow…!

You better believe there’s going to be another post about this soon…

*************

Vidal is a student who attends Mott Hall Bridges Academy, a middle school in Brownsville, Brooklyn. I know this because over the last week, I have become acquainted with this young man, the school he attends, Ms. Lopez (his principal), some of the teachers at the school, and his mother and siblings. I am one of several million people who came to learn about this young man – and the constellation of people to whom he is connected, who impact him and in whose lives he has made and continues to make an impression* – as a result of a photograph taken Brandon Stanton, the photographer behind “Humans of New York.”

The story goes like this: Stanton is a street photographer who launched “Humans of New York,” a photo project in which he aims to photograph everyone in New York City. He shares his photographs on his blog and his wildly popular facebook page, which is where I first encountered his work and he had a mere few thousand followers. (That number is now nearly 12 million.)

Brandon Stanton is a bond trader turned photographer who has captured and captivated people’s attention with the simple act of creating photographic portraits on the streets of all five boroughs of New York City. But he does more than take people’s pictures. He engages them in a conversation, asks them questions, and, in the last year or so, he has been asking his subjects a rotating set of questions, among them:

- What is the saddest moment of your life?

- What are you most proud of?

- What do you want people to know about?

- What’s your biggest fear?

- Who has influenced you the most in your life?

One day last week Stanton asked the last question to a young man with whom he crossed paths in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn.

|

“Who’s influenced you the most in your life?”

“My principal, Ms. Lopez.”

“How has she influenced you?”

“When we get in trouble, she doesn’t suspend us. She calls us to her office and explains to us how society was built down around us. And she tells us that each time somebody fails out of school, a new jail cell gets built. And one time she made every student stand up, one at a time, and she told each one of us that we matter.”

|

|

“When you live here, you don’t have too many fears. You’ve seen pretty much everything that life can throw at you. When I was nine, I saw a guy get pushed off the roof of that building right there.”

|

Of the many stories that could be told about this interaction and the series of stories and events that have unfolded since, I am most curious to know why young Vidal stopped to talk to Brandon that day.

At a time when differences among strangers are more liability than possibility, the likelihood of a young man taking up the invitation to talk by someone who does not look like him, outside of the (theoretically) safe walls of an institutional context like school, seems increasingly rare.

- Would there have been such an outpouring of support – in the form of comments and donations – if Vidal had been older? Didn’t smile?

- What if Vidal had selected someone other than Ms. Lopez as a big influence in his life?

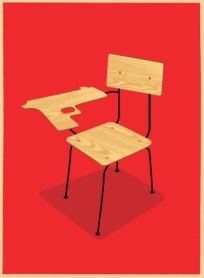

- How have the unsettling ways in which schooling is criticized, under-funded, and legislatively manhandled increased public sympathy for the daily work of educators and the young people with whom they spend their days?

- What impact do the ongoing discussions of #Ferguson, #EricGarner, and #BlackLivesMatter have on how people are seeing/reading/responding to Vidal and to the photo-action project he inspired Brandon Stanton to pursue?

- Did Juno (the Blizzard that could), by keeping many people at home, inadvertently drive the total closer to one million dollars?

The story has been picked by various news outlets and some of the descriptors used to tell the story (and the images and meanings they are meant to evoke) make me bristle. But I am forcing myself to weigh the bristling against the humanizing narrative that has unfolded from a single interaction – the HONY page is filled with portraits of other teachers from Mott Hall, follow-up images of Vidal, including a photo of him with his mother and brothers.

Following a conversation with Ms. Lopez, the subject of Vidal’s first interaction with Stanton, the photographer decided to tap into his millions of fans to launch a fundraiser to support some of the principal’s goals for her school and students (whom she calls scholars), among them: taking her sixth graders on a trip to Harvard and funding a summer program. The results have been staggering: the goal of $100,000 was raised in one hour. (Read the fundraising page for more info on what the monies will be used for.)

Stanton is doing two things at once with his larger HONY project: bringing forth the extraordinary that lurks behind any human encounter, while at the same time rendering ordinary that which may have been viewed only through extraordinary or sensational lenses. The photograph and the accompanying snippets of story, borne out of these human interactions, humanizes strangers and invites other strangers to recognize a glimpse of something familiar. We all have sad moments, fears, and people who have influenced us. HONY urges its fans and followers to slow down long enough to recognize the same in others, if only for a fleeting moment.

Famed photographer Gordon Parks, in a series of photographs that has been circulating recently and which are on display at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, similarly sought to depict ordinary Black life for an assignment for Time Magazine. Time never ran the images. An excerpt from the Slate magazine article on the collection suggests why:

“In this period, Life stories were told through the framework of the white middle-class American family. When stories did appear about African-American subjects, they were either about celebrities or athletes or people in very dire straits. Parks set out with this project to really counter those stereotypes.”

I read this article the day before Vidal appeared on my Facebook feed and so the two pieces seem intertwined to me: the pursuit of rendering the extraordinary in the quotidian and offering the dignity of the ordinary to everyone.

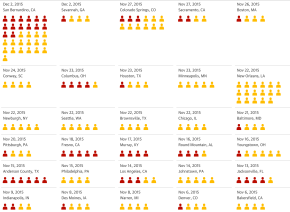

Regardless of why and what additional questions this story raises (this could be the subject of another post — on how education is valued, funded, supported; whose humanity is recognized, in what ways, and how we might nurture this inclination in friends and strangers, alike…), Vidal, Ms. Lopez, and the story of Mott Hall, rendered in photographs and story bits, has moved many of us – over 30,000 people have donated to the fund raiser already.

At the time of this writing, the total is $873,550 $877,477 $877,477 $877,771 $883,226 $893,512 $895,803 $929,094 $943,850 $948,990 $950,949 and increasing steadily, with people donating every few minutes.

The donations seem to average $20, but the $5 – and even $3 – donations really lifted my spirits. I was momentarily caught up in a wave of Obama ’08 fundraising nostalgia, a campaign built on the idealism of the $5 and $10 donations. Every one can participate (provided you have a credit card).

Ok, I’m going to go and donate now before it reaches its first million.

Before I go, a few links that may be of interest:

The Humans of New York Blog

The Humans of New York Facebook Page

Mott Hall Bridges Academy website

The Indiegogo Fund Raising Page

A Pinterest Board (where I’ve curated all of the HONY portraits related to this story, as well as a number of relevant articles)

*I suspect the latter number has increased a few million-fold by now.